Jenny Winder's

excellent piece in the Washington Times (which I urge you to read) Sound and vision: Exploring the world of sight and hearing contains many fascinating, surprising, and intriguing examples of the peculiarities of human perception.

Jenny Winder's son, like my own, is colour blind and, using our knowledge of light and retinal biology, we can infer what our sons and people with different types of colour blindness see:

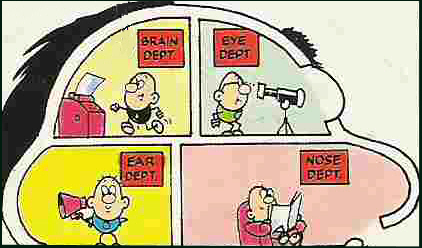

Now it is easy, when thinking about perception, to be led astray by a kind of "Numskulls" (from "The Beano") notion of psychology (I point to which I shall return)

where (in the case of vision) "I" is the little man top right with specs, and my sensory apparatus is the telescope, and "I" look at what appears in the eyepiece of the telescope. Such a notion of perception is clearly philosophically problematic (not least because it would lead to an infinite regress of little men with telescopes) and biologically incorrect. As Jenny Winder notes, colour perception is ultimately located in the activities of our brain cells - activities that take place in response to signals transmitted from the retina by the optic nerve.

It is, I suppose, possible that, just as various types of colour blindness affect the functioning of the retina, there could be biological conditions that affected the functioning of the optic nerve. Such conditions might, in turn, lead to new insights into what different people see when presented with different colours and these scientific insights could be added to what we understand about colour blindness; but I know of no such conditions.

When we get into the brain itself, however, there are further complications - which Jenny Winder alludes to. The science of observing and teasing apart neuronal activity in different people presented with different visual stimuli still has a lot of work to do. Perhaps one day (by analogy with the theoretical example of optic nerve function and the well understood example of retinal biology) we might be able to infer - from neuronal activity - what different people experience when presented with the same visual stimulus. Perhaps we never shall. But, given what Michael Stevens calls (in the video Jenny Winder links to) the "ineffably private" nature of colour vision, things get a bit murky at this point.

In his video (which is certainly worth a watch) Michael Stevens departs somewhat from a purely scientific analysis of this topic and ventures off into the realms of philosophy. One of my problems, with Michael Stevens is he makes no attempt to distinguish clearly between the two realms.

The Philosopher whose name most often crops up in this context and whose ideas would seem to inform Michael Stevens, is John Locke:

15. Though one man’s idea of blue should be different from another’s.

Neither would it carry any imputation of falsehood to our simple ideas, if by the different structure of our organs it were so ordered, that the same object should produce in several men’s minds different ideas at the same time; v.g. if the idea that a violet produced in one man’s mind by his eyes were the same that a marigold produced in another man’s, and vice versa. For, since this could never be known, because one man’s mind could not pass into another man’s body, to perceive what appearances were produced by those organs; neither the ideas hereby, nor the names, would be at all confounded, or any falsehood be in either. For all things that had the texture of a violet, producing constantly the idea that he called blue, and those which had the texture of a marigold, producing constantly the idea which he as constantly called yellow, whatever those appearances were in his mind; he would be able as regularly to distinguish things for his use by those appearances, and understand and signify those distinctions marked by the name blue and yellow, as if the appearances or ideas in his mind received from those two flowers were exactly the same with the ideas in other men’s minds.

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding by John Locke

We can forgive Locke for the fact that the science of perception was virtually non-existent in his day. This fact does not detract from the essence of the points he makes. But, like Michael Stevens, John Locke, I would argue, is in danger of conflating science and philosophy here.

If Locke is putting forward a scientific theory that the "different structure of our organs" might produce marigold in one man's mind and violet in another man's mind and that this "could never be known", he is simply wrong. Science has already provided a great deal of knowledge in this area and future science, I think we can assume, will provide a great deal more.

If, on the other hand, Locke is putting forward a philosophical theory, there is more to say.

I suppose the best way to illustrate the purely philosophical point would be to consider a situation where we have two people with identical sensory apparatus and identical brain activity when presented with certain colours (perhaps two identical twins). Here, though the scientist declares them to be the same, the philosopher can argue that, because perception is ineffably private, we still have no way of knowing whether these two individuals are having the same sensation when they look at (say) a strawberry.

Now, in this humble blog post, I cannot possibly do justice to the philosophical literature devoted to this kind of claim, but it's the kind of philosophical claim that clearly strikes a chord with many people and I think it is worth further examination:

First of all we have to be clear about what we mean by the word "same" here. Two twitchers who claim to have seen the "same bird" on a particular day may both have being sharing a hide and observing a single lesser-spotted grebe in the field in front of them, or may have been far apart and observing two different individual lesser-spotted grebes in different places. In the first case they observed the same token. In the second case the same type.

It is trivially true that two individuals looking at the same strawberry don't have the same (token) perception. They have different heads.

But do they have the same (type) perception? Does this question make sense?

The notion here seems to be that if the little Numskull in my skull could climb into your skull and look down your telescope he would say "ah yes, that's just what I see in my telescope" or, alternatively, "hmmm, that's not what I see in my telescope". But, as has been argued, the Numskulls do not lend themselves well to coherent thought experiments.

If we tease out the purely philosophical claims implicit in John Locke's or Michael Stevens's accounts, we are being asked to assign meaning to contentions that two people might perceive different or the same (type) things in the absence of any criteria that could ever decide the matter. No conversations between the individuals will ever shed light on this question. No tests or scientific findings could ever shed light on the matter. We can't even think of a coherent thought experiment that could shed light on the matter - even extra sensory perception - were it to exist - would presumably involve the transmission of data from one brain to another which might then be interpreted differently.

I conclude that the essentially solipsistic position implied here - the only thing I can really be sure about is what's going on inside my head - is incoherent. I really can know (in the only senses of "know" that make any sense) - through science and through engaging with you - what is going on inside your head and when it is the same or different from what is going on inside my head.

This is a rather important conclusion. It means that none of us are truly alone.